Physiological Integration of Resistance Exercise During Energy Deficit

Understanding how resistance training interacts with the body's physiology during periods of energy restriction.

Overview of Energy Deficit and Muscle Tissue

Energy deficit—a state where caloric expenditure exceeds caloric intake—creates a fundamental metabolic condition that affects multiple physiological systems. When the body faces energy restriction, muscle tissue encounters competing demands: maintaining its structural and contractile properties while the organism mobilises substrates for systemic energy needs.

This section explores the physiological context in which resistance exercise occurs under energy limitation. The interaction between mechanical loading and restricted energy availability produces distinct adaptive outcomes across multiple metabolic pathways.

Mechanical Tension and Protein Synthesis Pathways

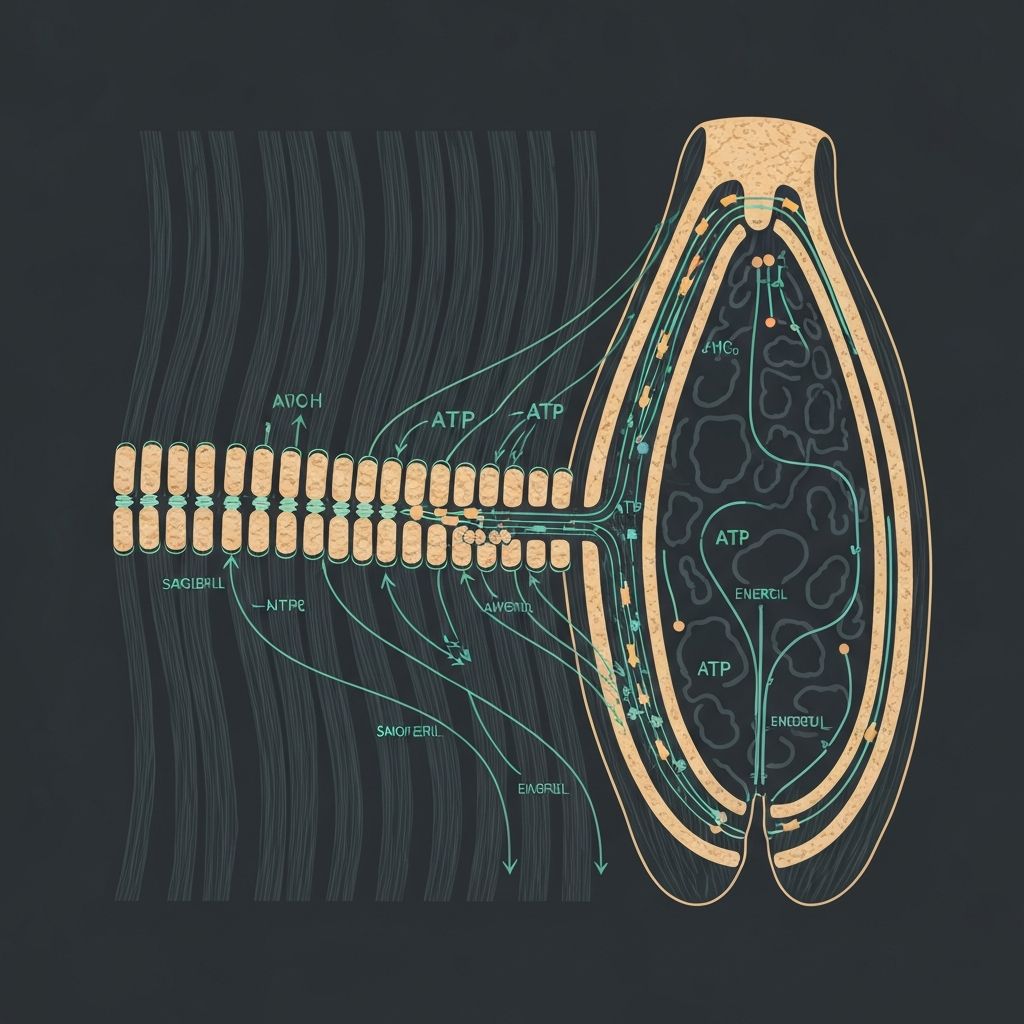

Mechanical tension generated during resistance training activates the mTOR pathway, a central regulator of protein synthesis. When load is applied to muscle tissue, mechanoreceptors and structural proteins sense deformation, triggering intracellular signalling cascades.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex phosphorylates downstream effectors, particularly ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) and 4E-BP1, which promote the translation of muscle proteins. This process occurs even when systemic energy availability is reduced, provided mechanical tension is sufficient.

Energy deficit modulates but does not eliminate mTOR signalling. The degree of tension applied to muscle determines the magnitude of mTOR activation, independent of the energy status of the cell. This principle suggests that resistance training preserves a capacity for protein synthetic stimulation despite caloric restriction.

Metabolic Stress Contribution During Deficit

Metabolic stress—accumulation of cellular metabolites such as phosphate, hydrogen ions, and metabolic byproducts—represents a secondary stimulus for adaptive signalling. During resistance exercise, rapid ATP hydrolysis and lactate production generate an acidic, phosphate-rich environment within the muscle cell.

The extent of metabolic stress depends on training variables including time under tension, rep ranges, and rest interval duration. Moderate to high-repetition schemes (8–15 reps) with shorter rest periods (60–90 seconds) maximise metabolic stress accumulation.

Under energy deficit, metabolic stress signalling may contribute to muscle preservation through activation of AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) and stress-responsive pathways. While AMPK generally inhibits mTOR, the acute stimulus from training overrides this suppression temporarily, creating a window for protein synthesis despite deficit conditions.

Energy Cost of Resistance Exercise

Resistance training contributes to total daily energy expenditure through multiple mechanisms. The acute energy cost during the exercise session itself represents the immediate ATP and substrate utilisation. For typical resistance training sessions (60 minutes), this acute cost ranges from 200–400 kilocalories depending on exercise intensity, muscle mass engaged, and training volume.

Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption (EPOC) extends energy expenditure beyond the exercise period. Following resistance training, the body remains in an elevated metabolic state for several hours, characterised by increased oxygen consumption and substrate oxidation. This recovery phase contributes an additional 10–20% above the acute exercise cost.

Chronic adaptations to resistance training also elevate Resting Energy Expenditure (REE). Increased muscle mass, enhanced oxidative capacity, and elevated mitochondrial density all contribute to a higher baseline metabolic rate. These chronic effects accumulate over weeks and months of consistent training.

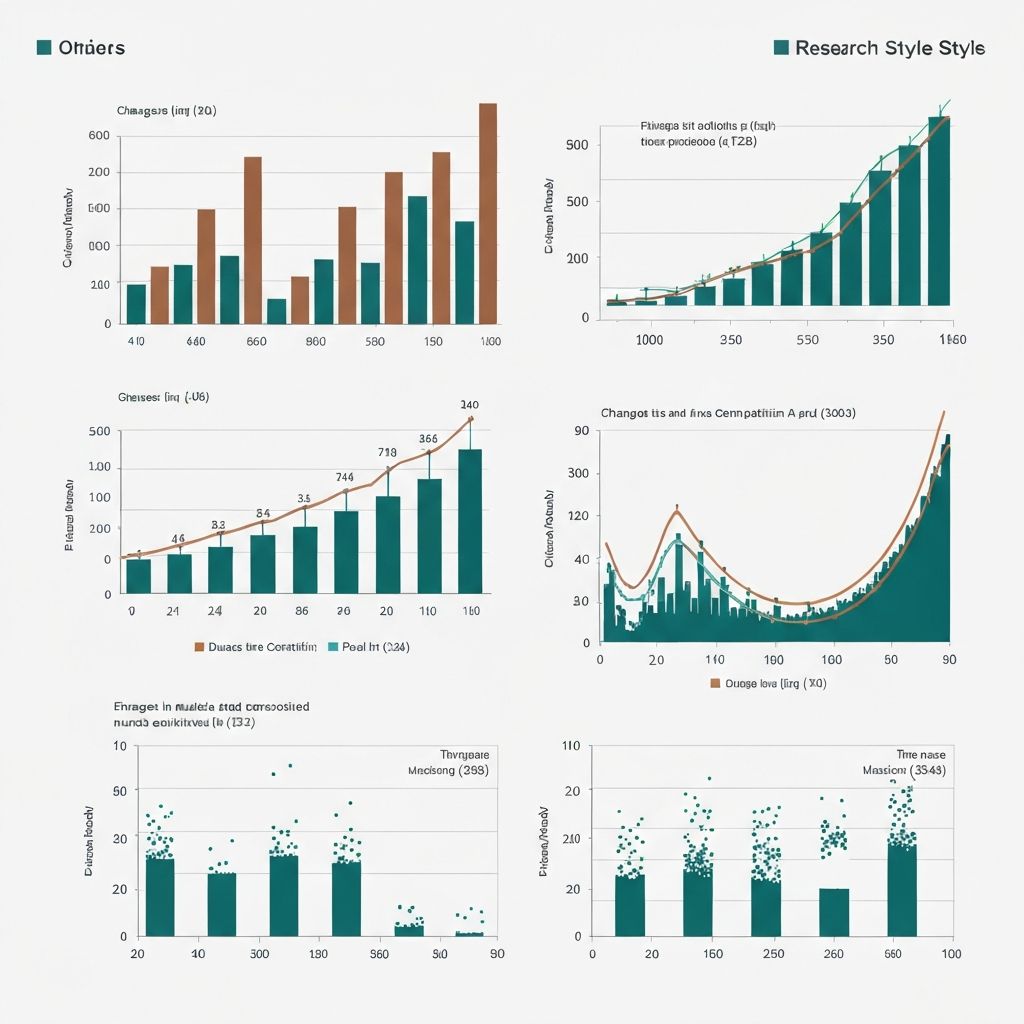

Changes in Strength and Muscle Mass Observed

Research examining the combined effect of energy deficit and resistance training reveals nuanced outcomes regarding strength and muscle mass.

| Study Parameter | Deficit Magnitude | Training Type | Muscle Mass Change | Strength Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate Hypocaloric (500 kcal/day deficit) | 15–20% below maintenance | 3–4x/week resistance, high load | -1 to +1% | +2 to +5% |

| Severe Hypocaloric (750 kcal/day deficit) | 30–40% below maintenance | 3–4x/week resistance, high load | -2 to -4% | +1 to +3% |

| Very Low Energy Availability | Greater than 45% deficit | Resistance training present | -5 to -10% | -2 to 0% |

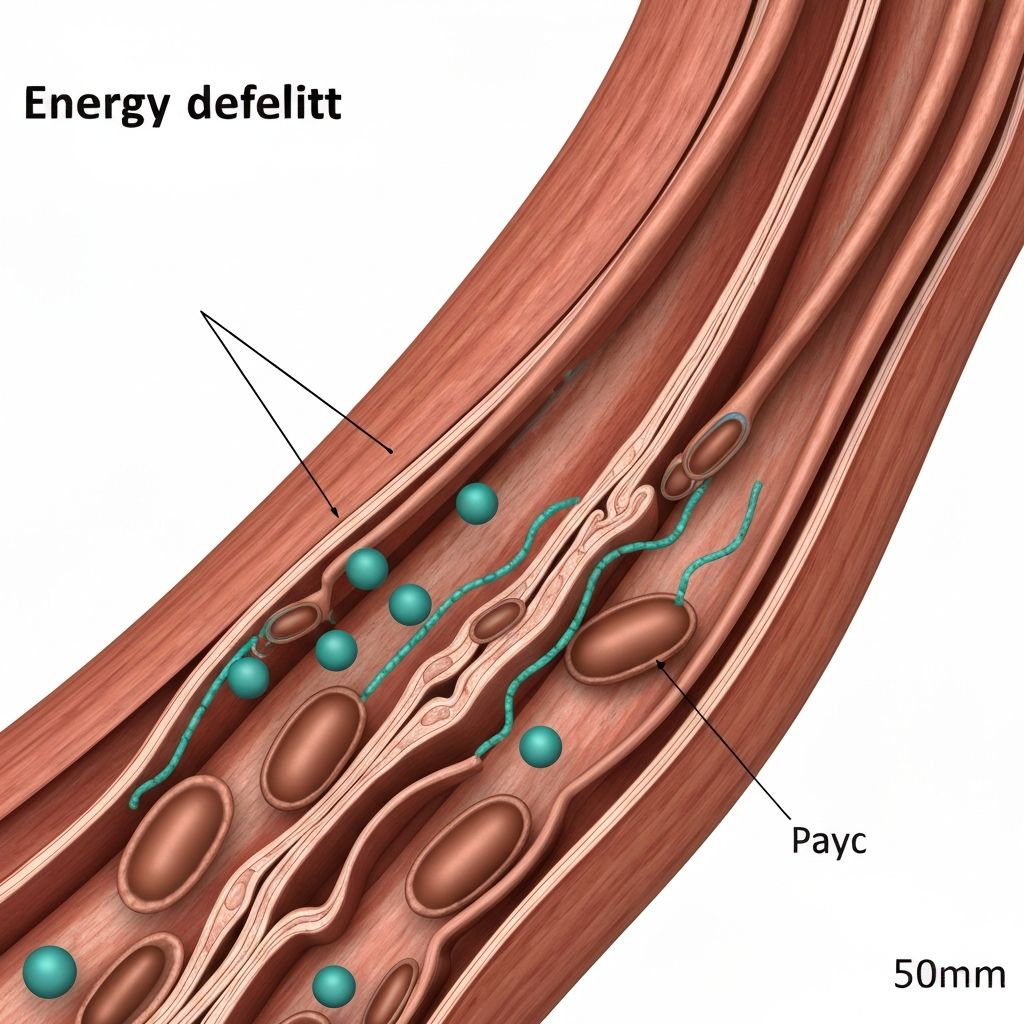

Lean Mass Preservation Mechanisms

The preservation of lean mass during energy deficit relies on several integrated mechanisms. Protein turnover—the balance between muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and muscle protein breakdown (MPB)—forms the foundation of mass preservation.

During energy deficit, basal muscle protein breakdown often increases due to elevated proteolytic activity via the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Simultaneously, basal muscle protein synthesis may decrease secondary to reduced amino acid availability and mTOR signalling suppression.

Resistance training acutely elevates muscle protein synthesis rates above baseline, creating a net positive protein balance in the post-exercise window. This acute synthesis elevation can persist for 24–48 hours post-exercise, especially when adequate protein intake accompanies training.

Sufficient protein intake (approximately 1.6–2.2g per kilogram of body weight daily) supports this balance by providing the amino acid substrate necessary for MPS. The mechanical and metabolic stimulus from resistance training sensitises muscle tissue to this amino acid availability, enhancing the synthetic response.

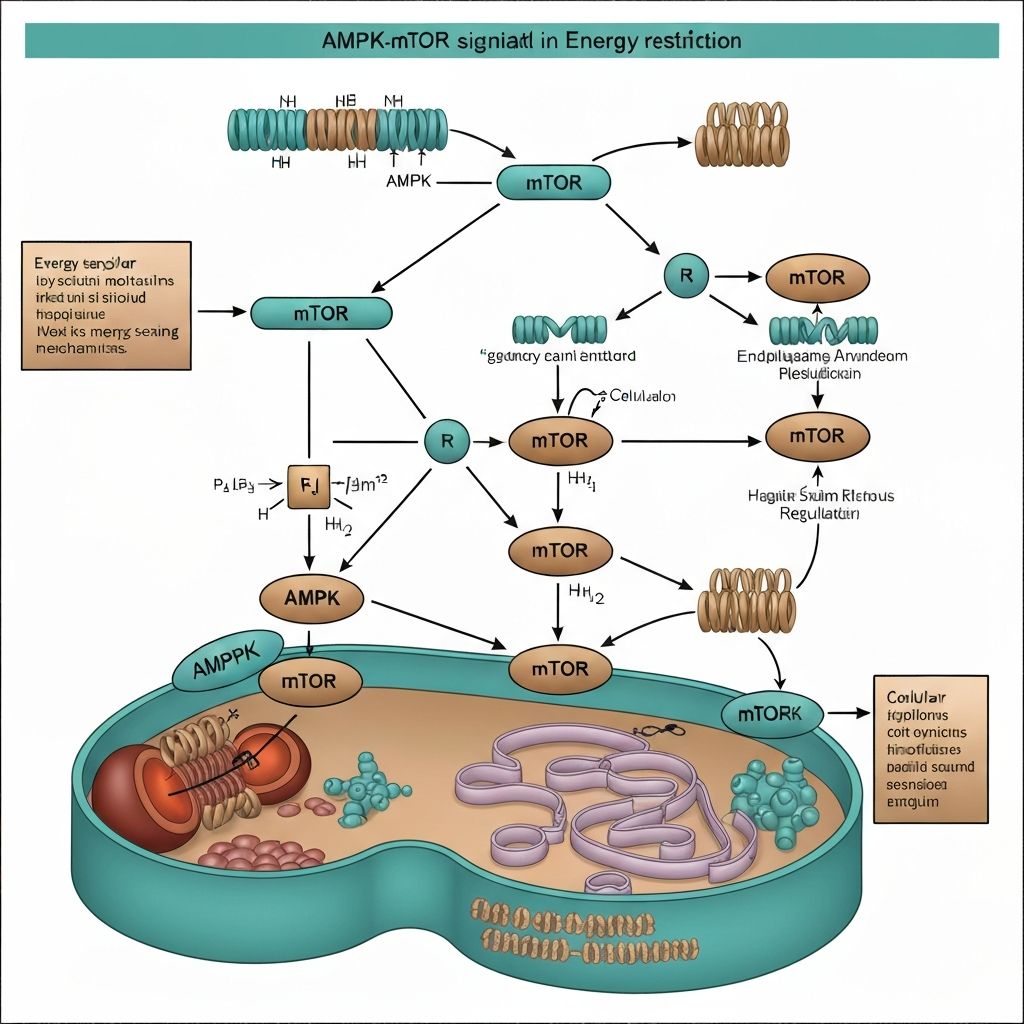

AMPK-mTOR Interaction in Restriction

The relationship between AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) and mTOR exemplifies cellular energy-sensing mechanisms. AMPK functions as a metabolic "fuel gauge," activated when AMP/ATP ratios rise—indicating energy depletion. Once activated, AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits mTORC1, suppressing anabolic processes and promoting catabolic ones.

Energy deficit elevates AMPK activity due to sustained reductions in ATP availability and elevated AMP levels. This state generally favours catabolism and inhibits growth pathways, presenting a theoretical challenge to protein synthesis maintenance.

However, resistance training acutely generates mechanical and metabolic signals that directly activate mTOR independent of energy status. This "override" of AMPK suppression occurs through calcium influx, RhoA activation, and direct mechanical sensing by mTOR complexes. The result is a temporary window of enhanced protein synthesis despite elevated AMPK activity.

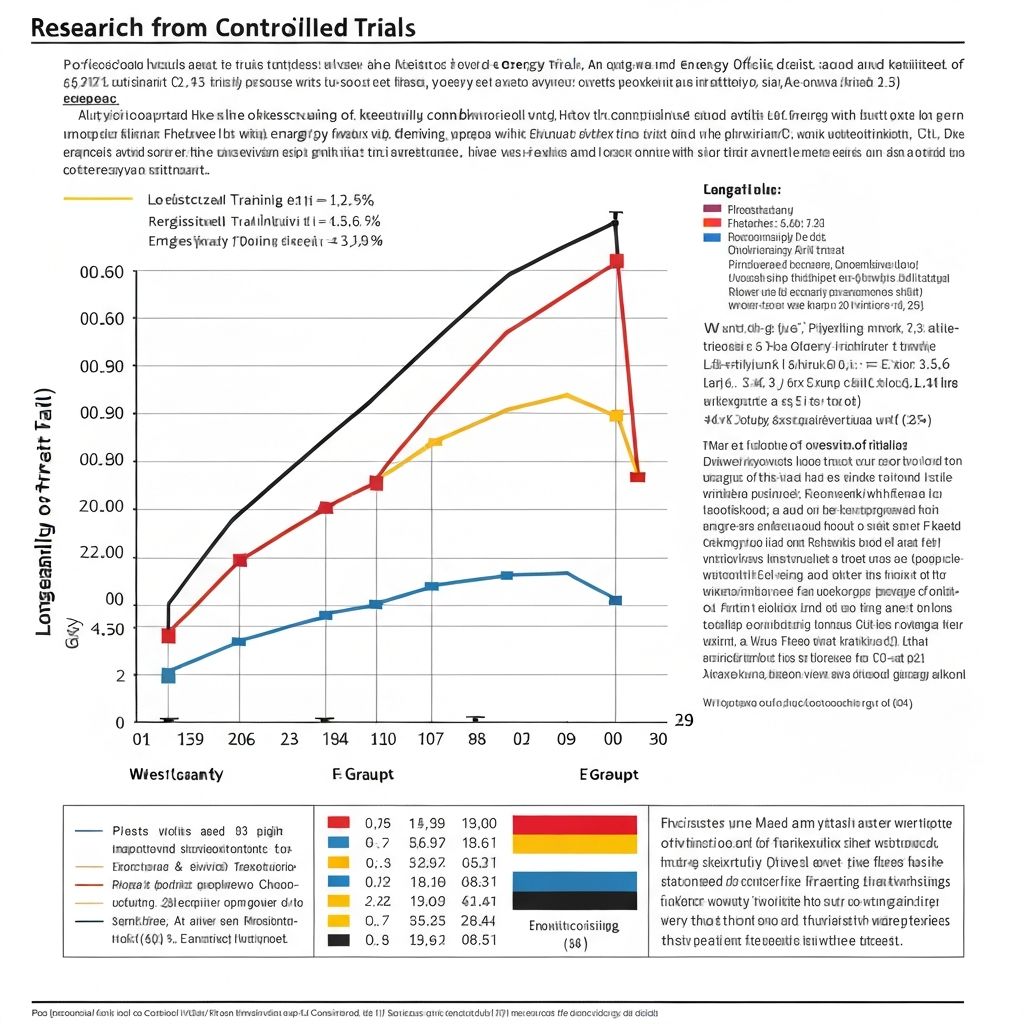

Longitudinal Data on Combined Interventions

Controlled trials examining sustained combinations of energy deficit and resistance training over 8–24 weeks provide empirical observations on adaptive outcomes. These studies typically employ randomised designs comparing energy-restricted conditions with and without resistance training.

Key observations include: (1) lean mass loss is substantially reduced when resistance training is included versus diet-only conditions; (2) strength maintenance or modest improvement occurs despite negative energy balance, particularly in untrained or moderately trained populations; (3) fat mass loss accelerates when resistance training accompanies deficit, likely due to enhanced total daily energy expenditure and post-exercise metabolic elevation.

Duration-dependent effects emerge: shorter interventions (4–8 weeks) show greater preservation of lean mass and strength, whilst longer interventions (16–24 weeks) reveal progressive lean mass loss even with training, particularly under severe deficits. This suggests that whilst training attenuates losses, prolonged severe restriction eventually overrides the protective effect.

Links to In-Depth Resistance Physiology Articles

The following articles explore specific mechanisms and research evidence in greater detail. Each examines a distinct physiological aspect of resistance training in energy-restricted states.

Muscle Protein Synthesis Regulation During Energy Restriction

Detailed exploration of anabolic signalling pathways, mTOR regulation, and protein turnover dynamics in hypocaloric conditions.

Read the detailed physiological explanationMechanical Tension as a Stimulus in Energy Deficit

Analysis of how load application generates adaptive signals independent of energy status, with focus on tension magnitude and training variables.

Learn more about resistance adaptationsStrength Adaptations in Hypocaloric States: Research Data

Summary of longitudinal research findings on strength changes, neural adaptation, and mechanical factors during energy restriction with training.

Explore energy deficit researchEnergy Expenditure Contribution from Resistance Training

Quantification of acute exercise cost, EPOC duration, and chronic REE elevation through resistance training adaptations.

Continue to related muscle physiology topicsAMPK-mTOR Crosstalk in Restricted Energy Availability

Mechanistic examination of metabolic sensing pathways, energy-dependent signalling switches, and training-induced pathway override.

Read the detailed physiological explanationLean Mass Outcomes in Combined Diet and Resistance Studies

Meta-analysis of clinical trial data examining lean mass preservation, body composition changes, and outcomes across deficit magnitudes and durations.

Learn more about resistance adaptationsFrequently Asked Questions

What is the primary physiological mechanism preserving muscle during energy deficit with resistance training?

Mechanical tension from resistance training acutely stimulates the mTOR pathway, enhancing muscle protein synthesis even when systemic energy is restricted. This stimulus is load-dependent and can persist for 24–48 hours post-exercise, creating a net positive protein balance window.

Does muscle mass always decline during energy deficit despite resistance training?

No. Lean mass change depends on deficit magnitude, training intensity, protein intake, and baseline training status. Moderate deficits (15–20%) combined with adequate protein and high-load resistance training often result in minimal lean mass change or modest gains, particularly in untrained populations.

How does AMPK activation during energy deficit interact with resistance training signals?

AMPK elevation during deficit typically suppresses mTOR-dependent anabolism. However, acute mechanical and metabolic signals from resistance training directly activate mTOR through calcium-dependent and mechanosensitive pathways, temporarily overriding AMPK suppression and permitting protein synthesis.

What role does metabolic stress play in muscle adaptation during deficit?

Metabolic stress contributes secondary signalling through pathway activation (e.g., calcium release, phosphate accumulation). Whilst not the primary stimulus compared to mechanical tension, metabolic stress may enhance adaptation and contribute to protective effects against lean mass loss during energy restriction.

Is there a threshold deficit magnitude beyond which resistance training cannot preserve lean mass?

Research suggests that severe deficits (greater than 40–45%) progressively diminish the protective effect of resistance training. Very low energy availability states create metabolic conditions where even intense training cannot fully prevent lean mass loss, likely due to systemic prioritisation of essential functions over muscle maintenance.

How does protein intake interact with resistance training during energy deficit?

Adequate protein intake (1.6–2.2g/kg body weight daily) provides the amino acid substrate necessary for post-exercise protein synthesis. Resistance training enhances muscle tissue sensitivity to amino acid availability, amplifying the synthetic response to protein intake during the post-exercise window.

Important Limitations and Context

This resource presents educational information on physiological mechanisms and research findings. The content is informational only and does not constitute personal recommendations, exercise guidance, or nutritional advice.

Individual responses to energy deficit and resistance training vary substantially based on genetics, training history, nutritional status, age, and numerous other factors. The observations presented represent general trends from population-level research and may not apply to any specific individual.

No outcome is guaranteed or promised. Changes in muscle mass, strength, or body composition depend on numerous interacting factors beyond the scope of this resource.

For decisions regarding personal health, nutrition, or exercise practices, consult qualified healthcare providers or registered professionals.